Introduction

One of the activities we take for granted as internet users is the ability to sign up to services. This process is common to just about every website and we rarely notice it as long as it works. But there are some interesting principles that underline user sign up and sign in.

So lets have a look at one implementation of a user system. This version is realistically quite simple, but it shows just how much complexity we overlook in just being able to log in to a website.

Stage One - Sign Up

Imagine you’ve found the most amazing website in the world. You can’t wait to get started doing whatever it is this website offers. You click on the sign up link. What happens next?

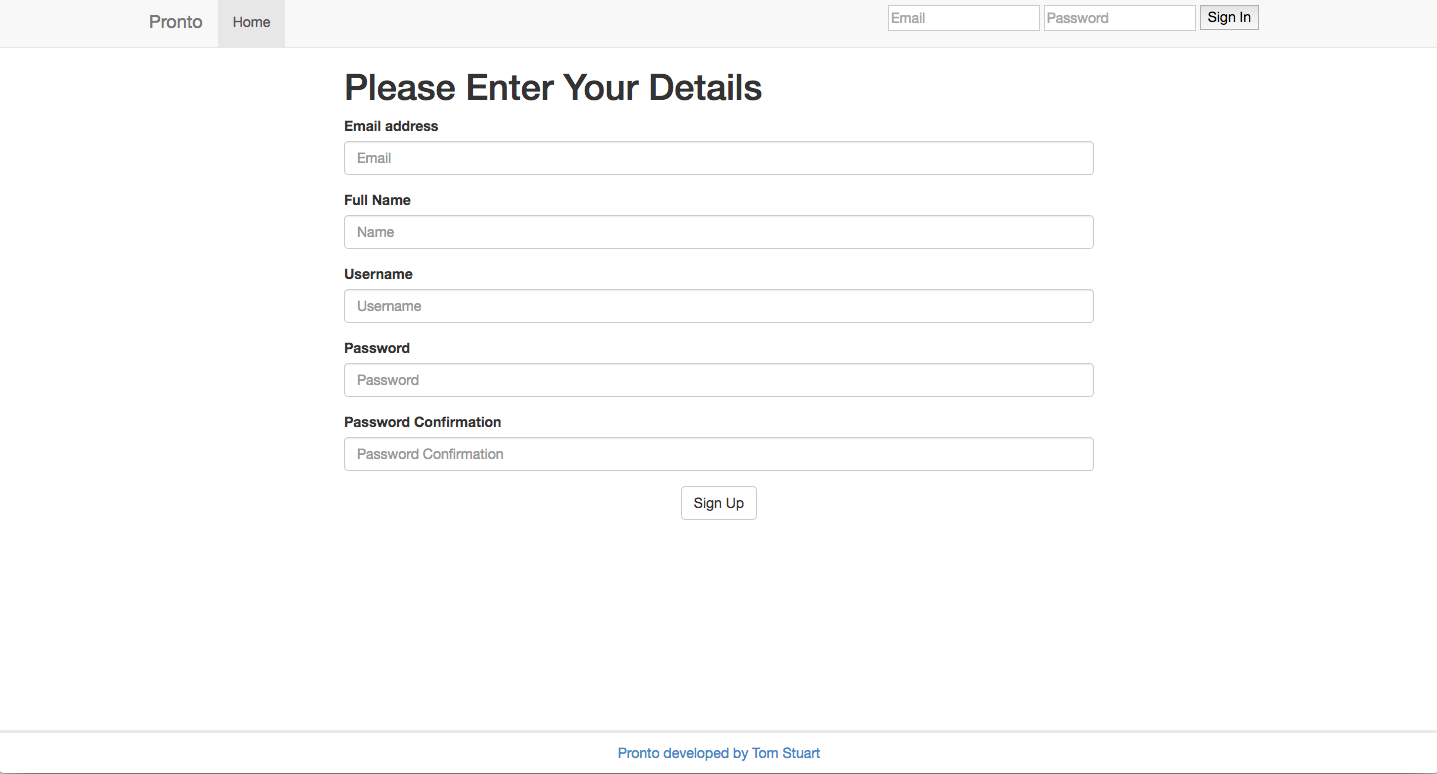

Well if its like 99.99% of websites on the internet you’ll probably be faced with something that looks a little like this:

This is a simple html form. Stripping away the visual aspects it looks something like this:

<form action='/users/signup' method='post'>

<label for="email">Email address</label>

<input type='email' name='email' placeholder = 'Email' required>

<label for="Name">Full Name</label>

<input type='text' name='name' placeholder = 'Name' required>

<label for="username">Username</label>

<input type='text' name='username' placeholder = 'Username' required>

<label for="password">Password</label>

<input type='password' name='password' placeholder = 'Password' required>

<label for="password_confirmation">Password Confirmation</label>

<input type='password' name='password_confirmation' placeholder = 'Password Confirmation'>

<button type="submit">Sign Up</button>

</form>

Simple right? We’ve got a label and input for each of our needed fields. When the user presses the Sign Up button a POST request is sent to the /users/signup URL.

But even here we have concerns. We’ve made each field required as an initial check on input, but this is not sufficient to protect our database as we’ll see later. We’ll have to add constraints to our database as well.

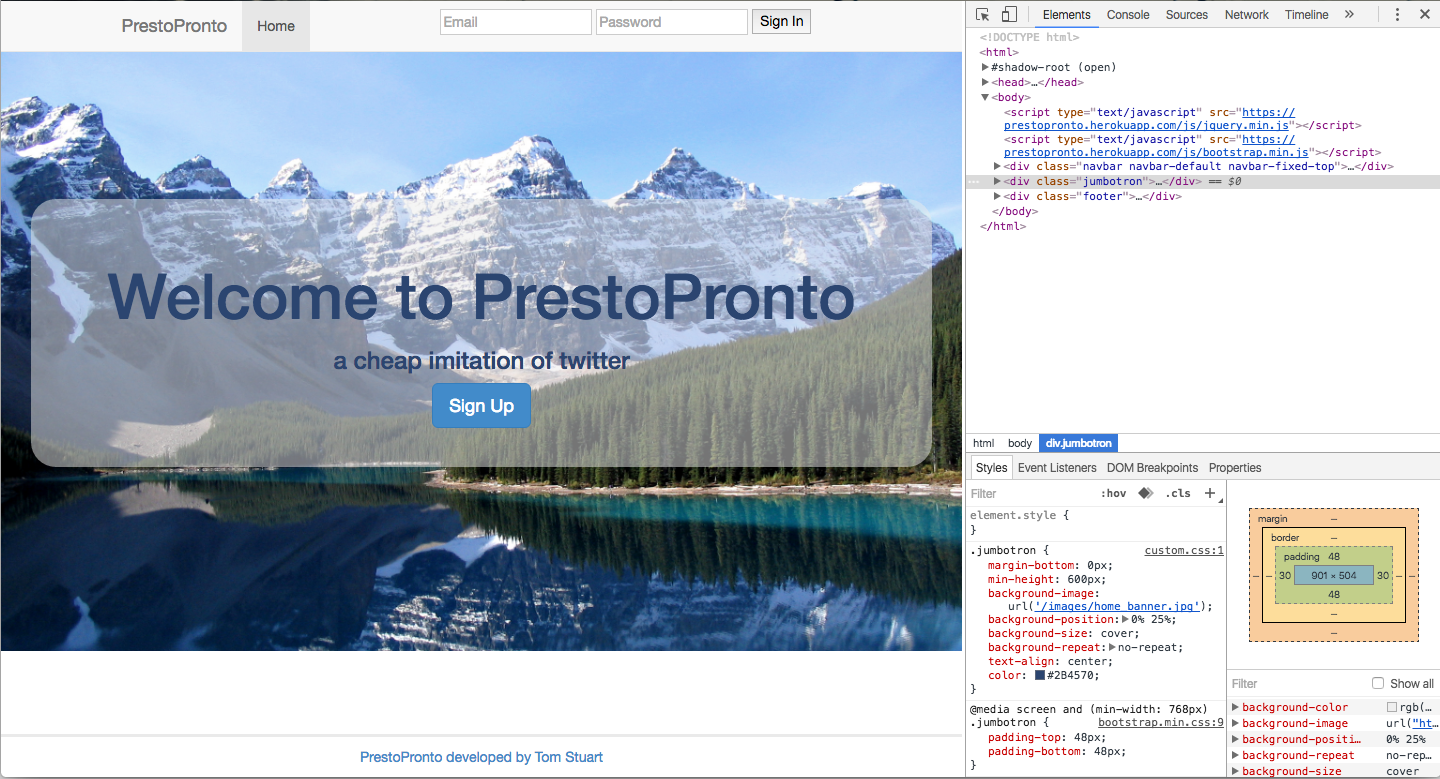

What about the password fields? How are they secured? Well one of the most useful tools I’ve found so far, is the google chrome developer tools. Once switched on in your preferences they allow you to interact with a web page:

The first tab shows us the html behind the site and lets us explore through the way the visual aspects are constructed.

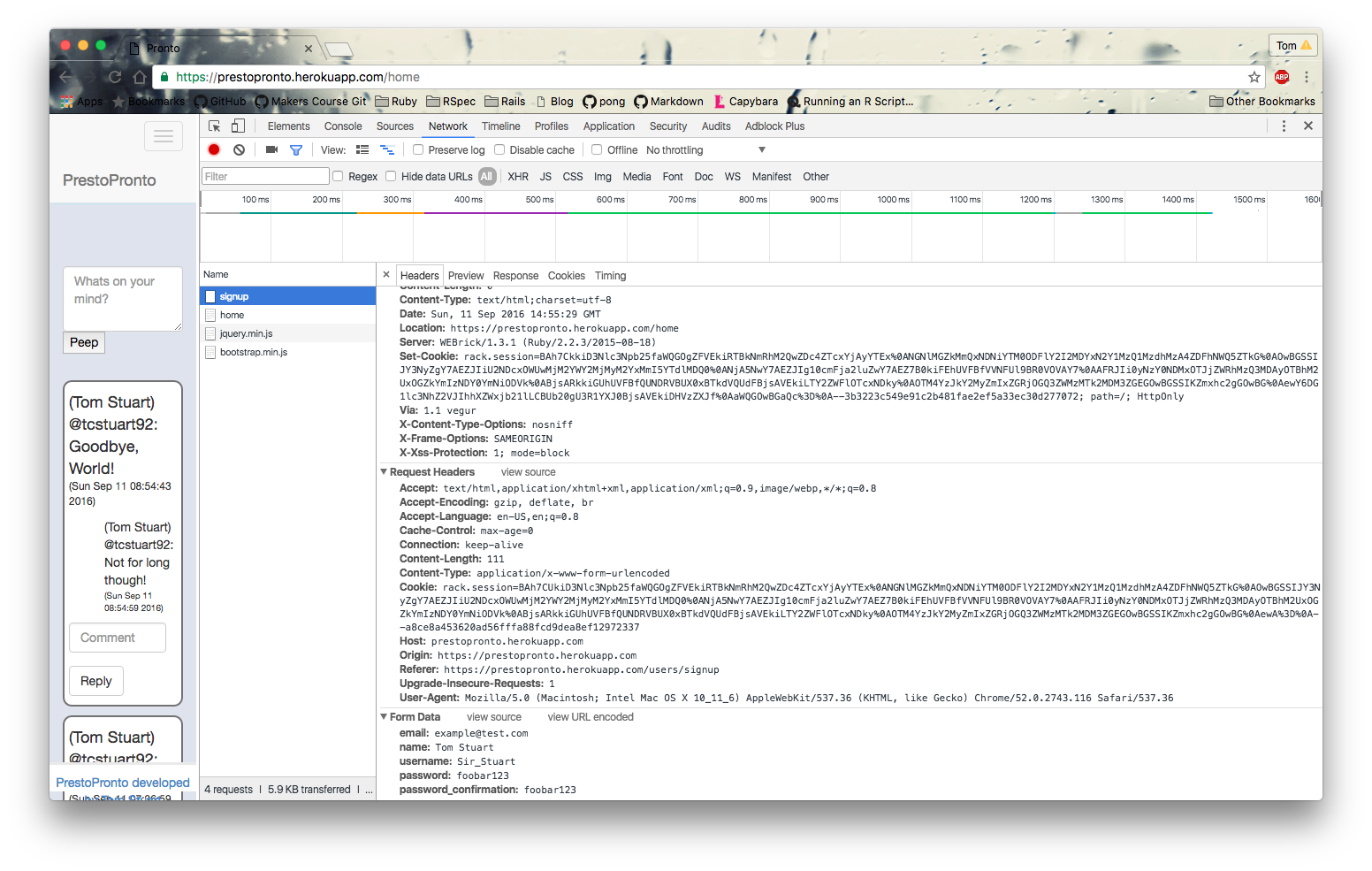

If we move to the network tab, we can watch all the requests our browser makes to the server. If we turn this on while we sign up we can see the POST request that is sent when the user clicks sign up:

This page is full of interesting stuff, but at the bottom we see this:

Our password is shown as plaintext in the request! How can that be secure? These are the concerns we need to have as web developers. Luckily here we are saved by SSL. If you look carefully at the above, you’ll see we’re using HTTPS protocols. This secures our connection between the server and the browser meaning its ok to pass along the plaintext password.

So the password arrives at the server, and we need to save it to the database. We could just save the string and be done with it. But what would happen if our database was ever hacked? The hacker would have immediate access to all the accounts. Instead we do something much cleverer and a whole lot more interesting.

Stage Two - Salting and Hashing

Before we begin, I’m going to introduce Cryptographic Hash functions. This is one of those topics that you can go down the rabbit hole as far as you want to go.

For our purposes, all that you need is to think of these as a black box that take in your password string and output a different random string. The important thing is that you can only go one direction, we can not feasibly take the output and get back the input.

Ok so we’re going to use one of these blackbox magic machines to secure our passwords. Luckily there are plenty of far smarter people out there who build these for us. The actual algorithms are designed by places like the NSA, yes the actual NSA in America. In ruby, we can use a gem called BCrypt which implements this algorithm in a more manageable way.

So we get our plaintext string. We’ll pass in into the machine and get a new hashed version out which is what we’ll add to the database.

As an example:

input = 'foobar123'

output = BCrypt::Password.create(input)

output = $2a$10$sS7nYmEI5xQ8hFM9X1rvvemqb4HsYWiwGtoeIIrKvytxGp8bSya1q

As you can see the output is unrecognisable as the input. In fact the output contains a few pieces of content:

$2a$10$sS7nYmEI5xQ8hFM9X1rvvemqb4HsYWiwGtoeIIrKvytxGp8bSya1q

$2a - The version of the Cryptographic function BCrypt has used. There are six different versions which become stronger as the number increases. 2a is the default version, and uses a implementation of crypt_blowfish to do the encryption.

$2a$10$sS7nYmEI5xQ8hFM9X1rvvemqb4HsYWiwGtoeIIrKvytxGp8bSya1q

$10 - The cost factor used. This allows us to tune our encryption on a scale of speed and security. The longer the encryption takes the more secure it is, but too long and it begins to impact the users experience.

$2a$10$sS7nYmEI5xQ8hFM9X1rvvemqb4HsYWiwGtoeIIrKvytxGp8bSya1q

The rest is the result of the encryption. Actually again it’s slightly more complicated than that.

This is where salting comes in. Instead of just passing your string into the algorithm, what BCrypt does is to add a random string to the start of your password. It then hashes this combined string.

The reason it does this is to improve security and if you want to read up about it have a look into rainbow tables. For now just know the string we get back includes the salt and the hash joined together in a single string.

The advantage of this is that if our database is hacked, the hacker only gets the hashed version of our users passwords. This means they still have to try to work out the original password to get in which is a really computationally expensive task.

Stage 3 - Log In

So you’ve signed up to your dream service and now you want to log in. You enter your email and password, and press the magic button. What happens next?

Well again the parameters arrive at the server. We need to check your password matches the one we have on record. However we just saved this as a hash; so a simple comparison won’t work!

Instead what we need to do is extract the salt from the password we have in the database. We then add it to the password you’ve entered in and hash it again.

If you have the same input string, the magic machine will give you the same output, so we can then compare to see if you have the right password.

The BCrypt implementation of this seems entirely backwards:

BCrypt::Password.new(Database_Password) == Input_Password

At first glance this seems to be hashing our saved hash and comparing it to the input password. In fact its just a clever user of the ruby language.

As all gems are open source we can go to github to take a look at the source code.

Lets look at each bit in turn. So we have a Password.new method call first. We all know this calls the def initialize method of the class:

def initialize(raw_hash)

if valid_hash?(raw_hash)

self.replace(raw_hash)

@version, @cost, @salt, @checksum = split_hash(self)

else

raise Errors::InvalidHash.new("invalid hash")

end

end

def split_hash(h)

_, v, c, mash = h.split('$')

return v.to_str, c.to_i, h[0, 29].to_str, mash[-31, 31].to_str

end

The code is quite simple to understand. We take in a raw hash, and after checking its syntax is valid, we split the single string into its four parts, saving each to an instance variable.

So we now have a ruby object with four attributes. We then compare this using == to the plain string. That won’t work will it? Comparing a Password Object to a String will always be false won’t it?

Well here is perhaps the cleverest use of the ruby language. They’ve redefined what equals means:

def ==(secret)

super(BCrypt::Engine.hash_secret(secret, @salt))

end

#in BCrypt::Engine:

def self.hash_secret(secret, salt, _ = nil)

if valid_secret?(secret)

if valid_salt?(salt)

if RUBY_PLATFORM == "java"

Java.bcrypt_jruby.BCrypt.hashpw(secret.to_s, salt.to_s)

else

__bc_crypt(secret.to_s, salt)

end

else

raise Errors::InvalidSalt.new("invalid salt")

end

else

raise Errors::InvalidSecret.new("invalid secret")

end

end

Calling == on a Password object calls the self.hash_secret method. This method takes the salt from the password object and the string we compare it to and passes them to our blackbox algorithm to compare.

This is as deep as we’ll go down the rabbit hole today. Still I hope you can see the amount of complexity that lies behind a simple login screen.

Leave a Comment