Introduction

This week at Makers we learnt our second Language, Javascript. This was a lot of fun, and after getting over the initial learning curve, I can honestly say I’m a big fan. Suddenly the idea of being a full-stack Javascript developer has become an appealing possibility; but thats for another time.

In the meantime, I want to talk about a powerful tool that any developer should have in there toolbox when dealing with object oriented programming languages… Duck Typing.

This weekend we were set the task of writing a Javascript program that can keep track of the score of a bowling game. I purposely set out to really use Duck Typing as an integral part of my solution so in the remainder of the blog, I’ll walk through some example code from my solution which should show the advantages of duck typing and also provide a nice introduction to Javascript!

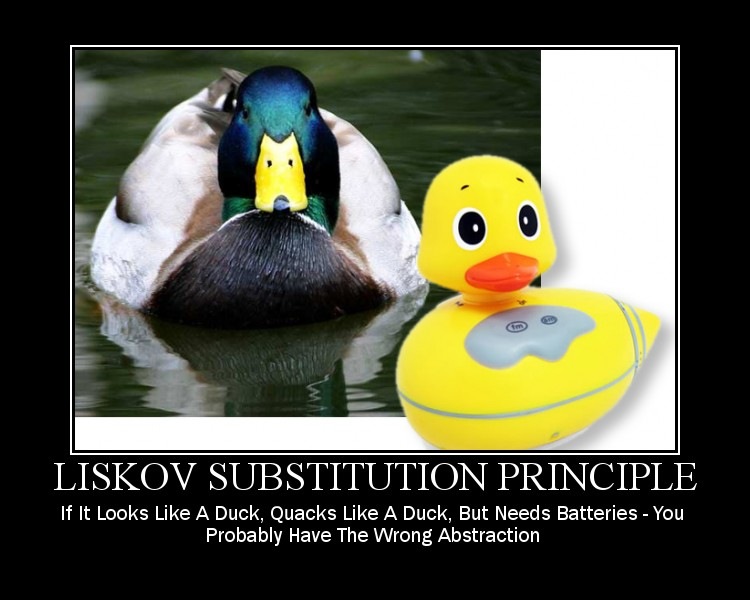

But Wait, What it Duck Typing?

If it looks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then its probably a duck.

The idea of duck typing, is that in dynamical languages like ruby and javascript, the language doesn’t care what the object it calls a method on is, as long as it understands that method call. Furthermore, we can substitute one object for another at runtime, allowing us to dynamically choose which object needs to be involved when the program is run.

For a simple example lets look at some ruby code:

class Duck

def fly

puts 'The Duck is Flying'

end

end

class Bird

def fly

puts 'The Bird is Flying'

end

end

array = [Duck.new, Bird.new]

array.sample.fly => 'The Duck is Flying'

Here we randomly choose an object by sampling our array. But it doesn’t matter which object is returned so we can call .fly on both. We say that these two classes are duck typed. They share the same public interface and so can easily be exchanged for each other.

So back to the main event.

In a bowling game, each players go is a frame. The frames have different rules depending on the circumstances:

- In each frame you have two attempts to knock down the pins.

- Except the final frame where you can have two or three.

- The score of the frame is the number of pins you knocked down.

- Unless the previous frame was a strike, where you get a 2x bonus on both your rolls.

- Or if the previous frame was a spare, where you get a 2x bonus on your first roll.

As you can see, while the abstract is the same (they are all frames), these different rules have different concretes (implementation of the rules). This is a prime candidate for duck typing. In my final solution I have four different duck typed frames:

- A normal frame

- A strike bonus frame

- A spare bonus frame

- A final frame

Each of these objects have exactly the same public interface but each have different implementations. For example lets look at how each class calculates its total score:

NormalFrame.prototype = {

// ... Excluded Code

calculateScore: function() {

return this.firstScore + this.secondScore

}

};

SpareFrame.prototype = {

// ... Excluded Code

calculateScore: function() {

return (this.firstScore * 2) + this.secondScore

}

};

StrikeFrame.prototype = {

// ... Excluded Code

calculateScore: function() {

return (this.firstScore + this.secondScore) * 2

}

};

FinalFrame.prototype = {

// ... Excluded Code

calculateScore: function() {

return this.firstScore + this.secondScore + this.thirdScore

}

};

As you can see, each object has the same public method name defined in its prototype. But each has a different concrete implementation of the way it calculated its score. The real power of this is when we come to calculate our total game score. We have a game class that keeps track of all the frames in a single game:

function Game(frameClass) {

this.frameClass = {frame: NormalFrame, strike: StrikeFrame, spare: SpareFrame, final: FinalFrame};

this.framesHistory = [];

}

Game.prototype = {

_currentFrame: function () {

return this.framesHistory[this.framesHistory.length-1]

},

_nextFrameType: function () {

if (this.framesHistory.length === 0) {return 'frame'}

else if (this.framesHistory.length === 9) {return 'final'}

else {return this._currentFrame().frameResult()}

},

nextFrame: function () {

this.framesHistory.push(new this.frameClass[this._nextFrameType()]());

},

addScore: function (score) {

this._currentFrame().addScore(score);

},

calculateGameScore: function () {

var scores = this.framesHistory.map(function(frame){ return frame.calculateScore()});

return scores.reduce(function(a, b) { return a + b; }, 0);

}

};

The first interesting thing, is our object in the this.frameClass. It contains each of our object constructors. When it comes time to make a new frame with the nextFrame() method, we dynamically choose which type of frame is needed next, based on the current game conditions as governed by the _nextFrameType() method.

Once we add the next frame to the this.framesHistory array, we can add scores to it by selecting the right frame, and then simply call .addScore() on it. We know that because our frames are duck typed they all have this method, and will add the score in the way appropriate to that circumstance.

Finally when it becomes time to calculate the game score, we simple iterate through our frame history. Firstly we map each frame to its total score. This again uses the duck typing. Each frame will calculate its total differently based on what sort of frame it is. But our game class doesn’t care, except that the calculateScore() method returns some integer. Once we have all our individual frame score, we can then use reduce() to add all the scores together.

We’ve successfully managed to abstract away the specific concretes into individual classes. Our game class is wonderfully simple, and is only loosely tethered to the specifics of the bowling frames. As long as each frame continues to have the same public interface, it won’t care how it implements its methods. If the rules of a bowling game change, it will only take minimal work to update our model.

This is a good example of the advantages of duck typing. The final product is as always hosted on Heroku, and I would recommend checking out the code if you want to see the full advantages of duck typing. I’ll add that this is by no means the optimal solution, but as an exercise in the advantages of duck typing, it remains a useful project in implementing object oriented design in javascript.

Leave a Comment